Does physical design influence the ideas people generate?

Context

In everyday life, people regularly reason about cause and effect.

What button turns on the TV?

What caused all of my plants to die?

To determine the most likely cause of an outcome, we must engage in a mental search for the best explanation. For example, after purchasing a new TV, you might have to guess which combination of buttons is necessary to find your favorite show. The combination you judge to be most likely is going to depend on your beliefs about how TVs work and on cues in the environment, such as the type of remote and its visual features.

Question

This project examines whether we can use physical design to constrain the ideas that people generate about causal relationships.

Can an object’s visible design influence the hypotheses a learner considers?

Impact

The physical features of an artifact may change the salience of various causes, influencing learning and discovery.

E.g., Visitors at a science museum might generate different explanations for the scientific phenomena they observe based on the physical design of the space.

Project Overview

Role: Project collaborator (2nd author): analyzed data, co-wrote manuscript, presented work at conference

Methods: A/B testing; statistical analysis; participants (both children and adults) completed 1-to-1 interviews in person

Challenges: Method had to be appropriate across the lifespan (i.e. for children and adults), and participants had to complete the study in person.

Literature Review

Through experience, learners develop beliefs about how causes and effects occur in the world. These beliefs can sometimes bias people to explain new observations in a way that is consistent with these prior beliefs.

Although design has not been specifically examined in the case of causal learning, there are reasons to expect that the physical environment influences causal inference. For example, if a door has no handle, we infer that we should push, because otherwise a handle would have been added. Norman (1988) included such constraints as one of several principles of good design that impact reasoning about the intended use of objects.

In prior research, learners made inferences about the design of objects, given information about functions. Here, we ask whether they could perform a more challenging task—infer an unlikely causal rule given an object’s design.

A/B Testing

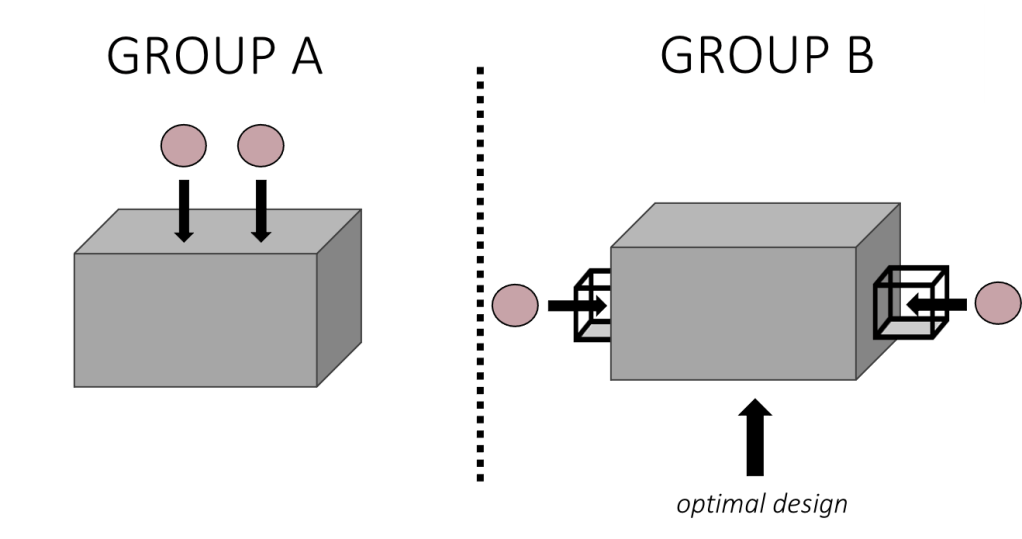

Comparison of which machine design makes it easier for adults to determine how the machine works.

Method: One-on-one interviews with children (3 years old) and adults.

Participants were shown a series of objects placed on a “machine.” Some objects made the machine play music, and some did not. The rule they had to figure out was that that the two objects were both necessary to activate the machine. We hypothesized that machine “B” made this rule more obvious as it appeared to be designed to hold two objects at once.

The design of the machine was different (and therefore the placement of objects as well) for Group A and Group B.

Group A: Machine was a cube and objects were placed on top.

Group B: Machine was a cube with transparent openings on each side, and objects were placed in these openings.

Participants were asked to report what kinds of objects made the machine play music, and to explain how the machine worked. We found that participants in Group B were more likely to correctly guess the causal rule of how the machine turned on.

Conclusions & Recommendations

Every learning environment (e.g. museums, classrooms, one-on-one instruction) should be carefully designed to facilitate the ideas and hypotheses learners come up with.

Design features can influence the ideas people generate, and can have major consequences for learning and instruction. The visible features of objects may increase or decrease the salience of the available evidence, and change the learner’s interpretation of their observations.